A reprint from Hunterdon Historical Record, by Russ Lockwood

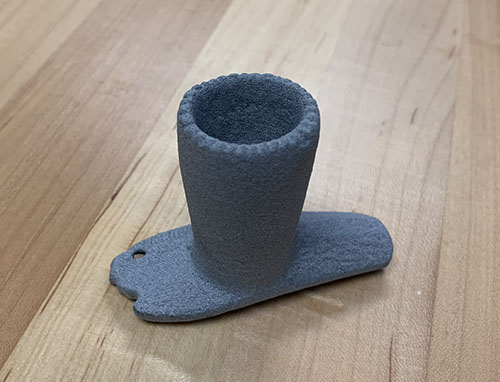

Tuccamirgan’s peace pipe and its two 3D replicas made with a 3D printer.

On October 19, 1925, the Case family donated a Native-American pipe made of soapstone to the Hunterdon County Historical Society (HCHS). Indeed, members of the Wickcheoche Tribe and Wickcheoche Council attended the donation ceremony at the Lenape Chief Tuccamirgan’s grave in the Case family cemetery on Bonnell Street in Flemington.

The pipe had been presented in the mid-1700s by Chief Tuccamirgan to Johann Philip Case (Kaes) as a Tuccamirgan’s per 3D replicas made token of friendship. Oral tradition relates that Tuccamirgan said he had lived in peace with his ‘blue brother’ and wanted to be buried in peace near him.

The pipe, known as a ‘monitor’ or platform type, measures about three inches long at the base with a bowl three inches tall. This type of pipe is believed to be from the Middle Woodland period — about 410 – 1180 AD. Thus, the pipe was possibly old before Tuccamirgan gave it to Case.

The idea of making a 3D replica of the pipe started with HCHS Trustee Roger Ahrens, who was taking classes at Raritan Valley Community College and contacted RVCC Program Coordinator Conrad Mercurious, who oversees the 3D lab as well as professional development and community service activities for the college. They first tried a spearpoint, but while it came out well enough, the differences between the original and replica were plain to see.

Mercurious put Ahrens and fellow HCHS trustee John Allen in touch with Cimquest, Inc., a value-added retailer of 3D scanners, printers, and software with headquarters in Branchburg, NJ and a half-dozen 3D printing facilities across Eastern and Midwestern US.

As Cimquest has state-of-the-art 3D equipment, Adrens and Allen worked with 3D Printing & Scanning Engineer Damon Johnson and Application Engineering Team Manager Jimmy Barrera on a plan to scan and 3D print Tuccamirgan’s pipe. Johnson noted the scanning and printing process proved routine except for the delicate handling of the artifact. Due to the age and fragility of the pipe, Barrera and Johnson opted for a Shining 3D Einscan HX blue light laser hand scanner that works well in scanning dark colors.

Johnson scanned the pipe four times, turning it gently in between each scan. The process took about an hour to generate the data, which was fed into Geo magic design X 3D software and massaged and post-processing stages. It needed about an hour to generate the final file needed for the actual printing.

The scan is accurate to 50 microns – that’s 1/2000th of an inch, or, put another way, a human hair is about 70 microns wide, although thicknesses vary among individuals. Fifty microns is also the threshold for eyeballing differences in objects.

The scanning was so accurate, it copied the hole and the partial hole at the ends of the pipe bowl. Inside the bowl, you can see the irregular Surface caused by the original carver. The bull’s serrated edge was faithfully reproduced. No one realized the black-colored pipe with gray mottling sported a hairline crack. Only after it printed in blue did they notice the crack.

Johnson fed the final 3D data into a Hewlett Packard Multi Jet Fusion which is HP’s version of powder bed fusion printing technology – faster than other powder bed fusion technologies like selective laser sintering or direct metal laser sintering. He printed the pipe as part of a batch of other printed objects on a mass-printing machine — not as a single object like home 3D printers.

Cimquest founder and CEO Rob Hassold presented the replicas and returned the original to Ahrens and Allen. The two replicas were sent to Gary Fogelman, a noted author and expert on Native-American artifacts, who matched the color and painted the pipe.

The original pipe is back in the archives. One replica is destined for display in the HHS’s second-floor museum in the Flemington Library. The other could be used for various show-and-tell events.

Leave A Comment