Reprint from 3dprint.com

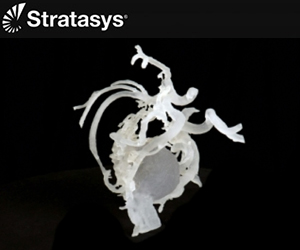

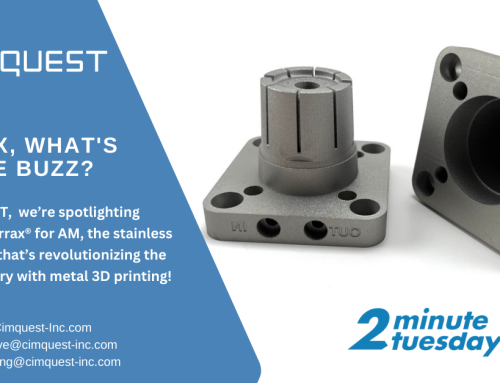

While most of us have either been the patient undergoing a surgical procedure or a loved one waiting and worrying, few of us have had to be on the other side as the trained surgeon, who often bears the responsibility of performing numerous delicate procedures with lives in his hands on a daily basis. Many of us are thrilled to hear about the innovations 3D printing offers to the medical world as people are saved with progressive implants and devices and quality of life is improved. 3D models are becoming more and more common not only for educating the patient on what is happening, but also for guiding surgeons in diagnosis as well as in treatment and the surgical process. Certain procedures may be completely new for a surgeon and while the 3D model is what he uses to study and practice on, it is probably the same 3D printed model that goes into the operating room with him and potentially shaves hours off the procedure, as well as plenty of stress.

As is common in hospitals after using 3D printing for one of these major procedures, the surgeons plan to continue constructing 3D printed models as needed. While they may not need to draw on the equipment on a daily basis, certainly it gives surgeons a new level of enthusiasm and peace of mind regarding new procedures that are required. With the ability to take a better look, in 3D, and the ability to practice until they have it down, everyone benefits all around. It’s also in cases like these that everyone from patients and their families to many different members of medical staff and doctors become acquainted with 3D printing–and its wonders–when previously they were not. Discuss this latest use of 3D printed models for surgeries in the Surgeons 3D Print Models of Children’s Brains forum thread over at 3DPB.com. According to Boston Children’s Hospital, SIMPeds director Peter Weinstock, MD, PhD, was first author on the paper; co-authors were Orbach, Sanjay Prabhu, MBBS, FRCR, and Katie Flynn, BS, ME, all of Boston Children’s Hospital. The study was supported by the Lucas Warner AVM Research Fund and The Kids At Heart Neurosurgery Research Fund.

![Vein of Galen malformation displayed in 3D model [Credit: Boston Children’s Hospital]](https://cimquest-inc.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/vein.png)

![A 3D printed model displaying AVM [Credit: Boston Children’s Hospital]](https://cimquest-inc.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/3Dmodel.png)

Leave A Comment