Almost two millennia ago, a man in Roman Britain was executed by crucifixion. His skeleton was discovered in 2017 in Cambridgeshire, England. And now, thanks to the expert work of forensic imaging specialist Joe Mullins and Oqton’s Freeform software, we can see his face.

Mullins is a professor at George Mason University in Virginia in the United States. He also works for the forensic imaging unit of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The Producers of the BBC documentary turned to Joe for his expertise in forensics for this historic case.

“It’s one of the coolest, most remarkable cases I’ve ever been involved with by far,” Mullins says.

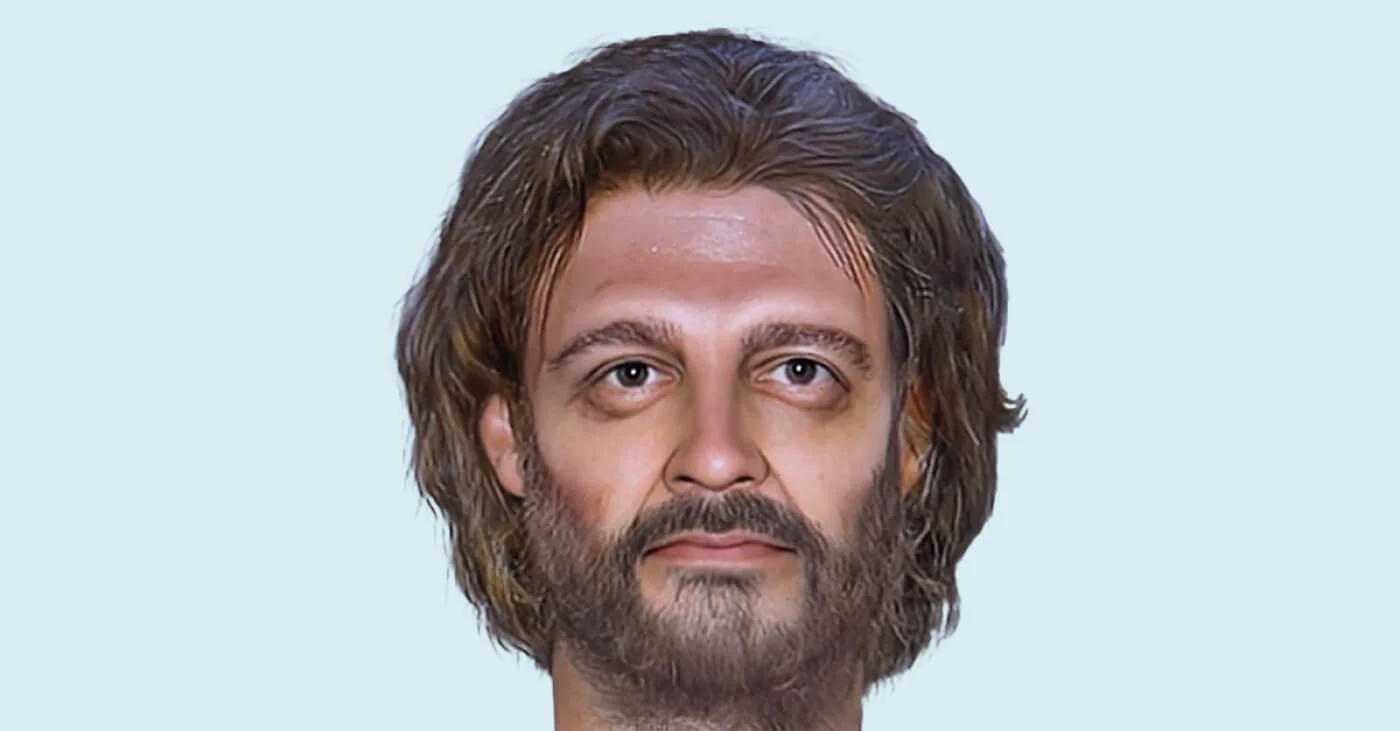

A facial reconstruction of a crucifixion victim. Image courtesy of Impossible Factual.

The details of the case are gruesome. The skeleton was discovered in a cemetery within a Roman settlement. The remains were unusual in that the heel was penetrated by a nail and the legs indicated the man was bound and shackled. According to radiocarbon dating, he died between 130 and 360 C.E. and was probably in his mid-30s. DNA tests suggested brown hair and brown eyes.

“They had a really captivating picture of the nail going through the heel, and the rest of the skeleton laid out on a blanket,” Mullins says. “I accepted their offer right away and immediately asked if they could provide photographs of the skull, so I could move forward on the facial reconstruction.”

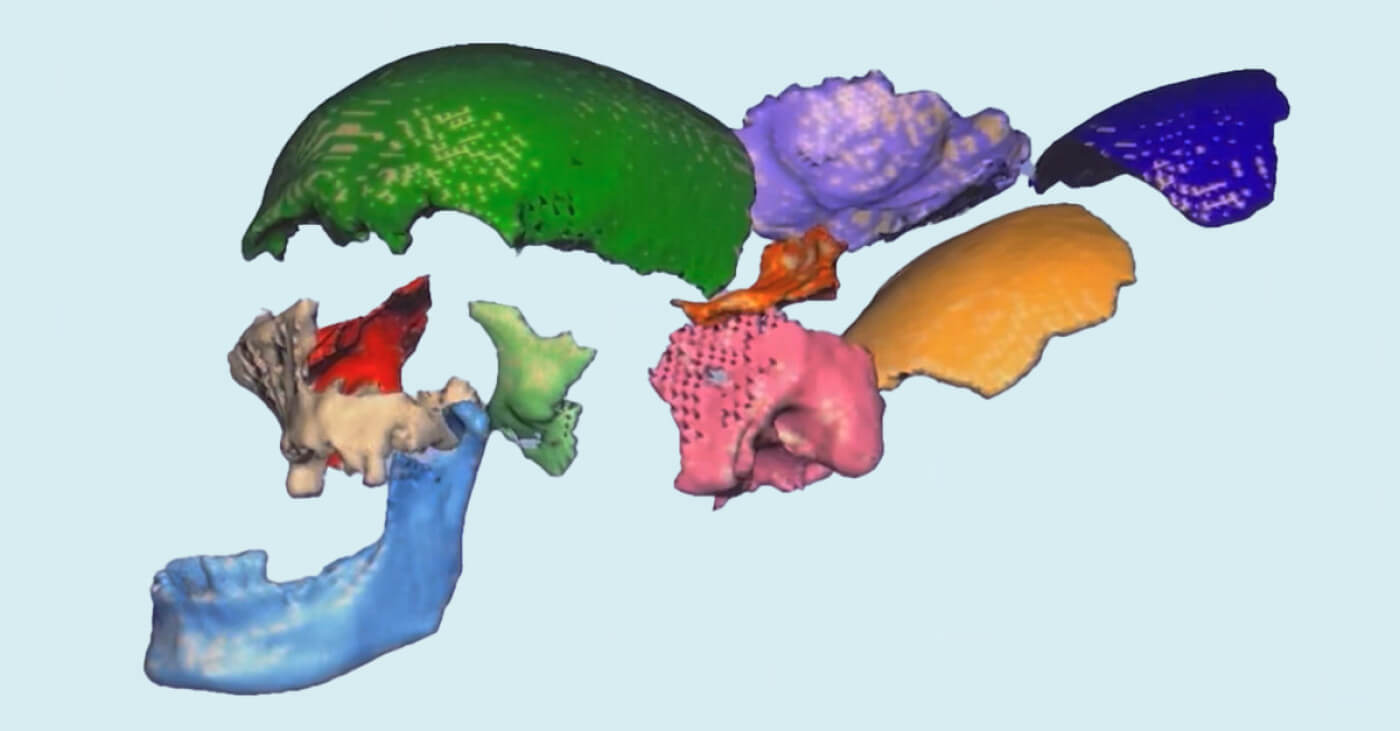

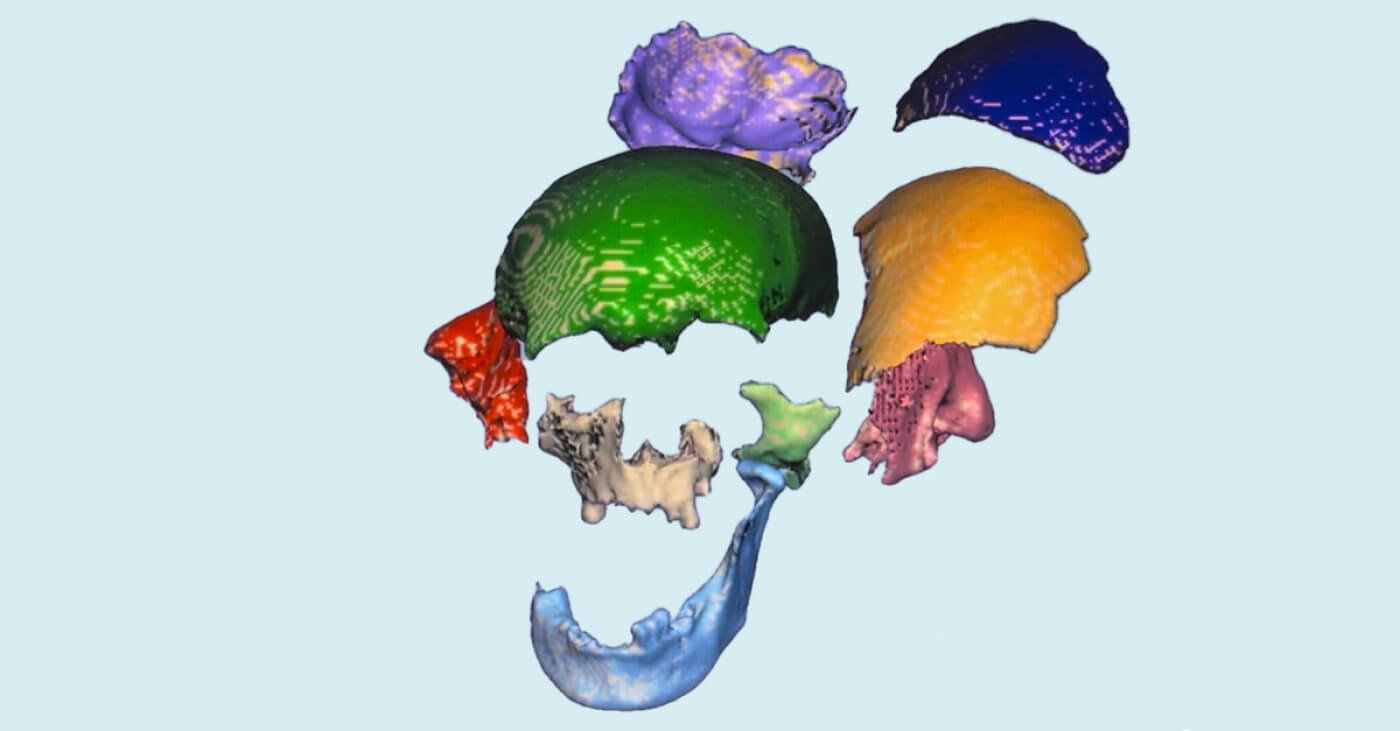

The first challenge Mullins faced was that the skull was not intact but rather in 12 separate pieces. After receiving the initial scans of the pieces, Mullins asked if it would be possible to reassemble the skull and rescan it. Unfortunately, it wasn’t. So Mullins turned to Freeform software from Oqton.

“Freeform is a major component of my work,” Mullins says. “The documentary crew just sent me a file, basically a jigsaw puzzle of the skull. In the software, I was able to individually reassemble the pieces digitally. Once the skull was reassembled, I could do a 3D sketch to get my projections for the placement of the nose and ears. I could put the grids on the skull itself.”

Facial reconstruction is a unique discipline in this regard because it combines art and science in equal measure.

“I’m essentially creating a portrait of a person from the inside out,” Mullins says. “The skull dictates the features of the face, the projection of the nose, the width of the nose, the thickness of the lips, even down to the eyelids, eyebrows, ears, and hairline. Using Freeform software, I work on one piece at a time and slowly reveal the face.”

One big advantage of working in a digital environment is that once the face is established Mullins can still see the underlying skull at any time.

“If I’m working in clay, I can’t see what I’ve covered up,” Mullins says. “I have to use a photograph of the skull for reference once the clay is in place. With Freeform, you just click the transparency button and toggle back and forth to make sure everything is where it’s supposed to be.”

Putting the puzzle together

As recently as a decade ago, working in clay was the norm for Mullins. Facial reconstruction started with photographs of the skull or skull parts, which were then brought together in a photo composite using Adobe Photoshop. This eventually segued into 3D approximations. In both cases, however, Mullins was using clay to sculpt the face on a replica of the composite skull.

But then one of Mullins’ mentors, forensic facial reconstruction specialist Dr. Caroline Wilkinson, who was at the time working for the Liverpool John Moores University’s School of Art and Design, made Mullins aware of Freeform.

“We realized that Freeform gave us a digital way of doing these facial approximations without clay,” Mullins says. “You’re starting with a CT scan of a skull, so you can bring that image into Freeform and manipulate it in the digital environment. It cuts the time in half, or more. You get a more accurate depiction because you can make the virtual clay transparent. You can see the surface you’re building on, so you don’t lose any detail. It’s just mind-boggling.”

Of course, Mullins did need to find a way to replace his favorite clay sculpting instruments. Instead, he now uses the unique haptic interface that works with Freeform.

“The haptic feedback is such a welcome aspect of the solution,” Mullins says. “You get the same tactile experience as sculpting.”

Mullins used Oqton Freeform to assemble the pieces of the crucifixion victim’s skull. Image courtesy of Impossible Factual.

But before all that can happen, Mullins must do the actual work of reassembling the skull digitally from its constituent parts. Typically, this happens with the OBJ or STL file formats. An STL file, for example, could be converted from the DICOM file of a CT scan. After import into Freeform, Mullins can start the process of connecting the pieces.

“For this project, I went through and separated them into individual layers and then made one piece solid, and then the next, and the next. I could feel it using the haptic device. It was just fascinating, seeing this 2,000-year-old skull come to life. I couldn’t have done it without Freeform.”

While Mullins is an expert in forensic facial reconstruction, he is not an osteologist or an anthropological expert in anatomy. So part of the experience involves comparing each piece of the skull to a reference photo to find a likely match.

“I would move each fragment around until I could identify it as the zygomatic arch, or a piece of the mandible, or the top of the skull,” Mullins says. “I can’t imagine doing that in the physical world. With Freeform, even if there is trauma to the skull, you can copy and flip and reuse the existing skull scan to fill in the missing parts. You can’t do that in the real world.”

Exploring the full functionality of Freeform

As a Freeform expert, Mullins has a lot of favorite features and functions, starting with the Freeform modeler.

“The Freeform modeler does so many things,” he says. “Whatever tool you want to use, everything you need is available. You can customize the size and do whatever you need to do.”

Another very helpful feature for Mullins’ work is the ability of Freeform software to duplicate and relocate features that come in pairs, like ears and eyes.

“Sculpting the ear with clay, you have to make two matching ones and then go through the process of attaching each one to your clay,” Mullins says. “With Freeform, I can do this 10 times faster. You flip it to the other side and you have two. This is also very helpful for setting the eyes in their orbits. Before, I had to use a marble in one orbit to get them both oriented. Now I can adjust the view and place each eye much more accurately. It’s night and day.”

Thankfully, all of these capabilities came together to reveal a distinctly haunting face from nearly two thousand years ago — one with a beard and dark brown eyes — giving us a surprising window into a very different time in the history of humanity.

“I will never forget staring at that face,” Mullins says. “And it wouldn’t have been possible without Freeform. It’s been a wonderful tool for me throughout my career.”

Image courtesy of Impossible Factual.

Contact us to learn how Freeform can help your business.

Leave A Comment